What was one of the biggest marketing failures in history?

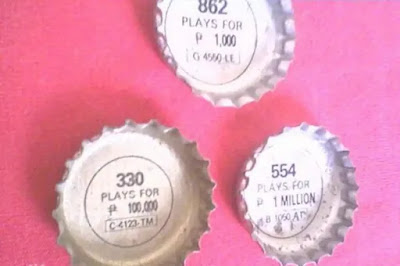

At the beginning of 1992, Pepsi decided to launch a "Number Fever" contest - people had to find three-digit numbers under bottle caps.

In the evenings, the winners were announced on TV, the prizes were not so big, about 100 pesos (~$5). On the last evening of the competition, they had to say the most cherished number (there were only two of them), which gave the main prize of 1,000,000 pesos (~$40,000), despite the fact that the salary of the average resident was then ~$100.

The Philippines by that time had long become the sphere of influence of PepsiCo's competitors, Coca Cola. In the Philippines, real public acceptance had yet to be won. Three-quarters of the local market was owned by Coca Cola. Then the producers of Pepsi developed a marketing plan that was supposed to draw attention to their own cola.

A few years earlier, in 1984, such a publicity stunt had already worked for the Latin American market. PepsiCo decided to repeat the success.

Every evening, a television program announced the winning numbers - starting from 100 pesos, which was about 4 US dollars. Most of the population of the Philippines was then engaged in hard physical labor, the minimum prize amount of the action was approximately equal to earnings per day. The maximum prize - one million pesos or $ 40,000 - for those participating in the lottery was a real jackpot. Such a large amount was the earnings of an ordinary Filipino for twenty-three years of honest labor. The lucky number should have been announced at the end of the promotion.

The action brought success, Pepsi sales grew every day. In the spring of 1992, the company owned almost a quarter of the market, after the four percent that were recorded in the winter. And the evenings of the Filipinos were now accompanied by bottles of cola with numbers under the cap and watching TV shows. Every day, except Saturday and Sunday, the winning numbers were announced on television with the amount that was due to the lucky ones. These numbers, which brought prizes of various sizes to the winners, were determined in advance, their list, in order to avoid abuse, was kept in a bank safe. By the end of the advertising campaign, more than 31 million people had already participated in it.

On May 25, it was announced that the winner of one million pesos would go to whoever found the number 349 under the lid. The problem was that there were 800,000 such lucky ones in the Philippines.

protests

Somewhere at the stage of preparing the competition, as a result of someone's oversight, or perhaps deliberate sabotage, even though this was not confirmed, there was a failure in the distribution of numbers by caps. The company thought of only one winner, only he had to see the coveted numbers.

It was out of the question to fulfill its obligations to the owners of caps with the number 349 - the company simply did not have such funds, because it was already about tens of billions of dollars. Pepsi had to pay $32 billion (!), people rioted on the street, more than 35 soda trucks were overturned and burned, Molotov cocktails were thrown at office windows, and at one point even a grenade that killed 5 people. The management of PepsiCo announced a mistake and a technical failure, but people who had already managed to believe in their luck did not accept such an excuse. Riots broke out in Manila. The company's headquarters were besieged by buyers who felt cheated.

Neither corruption, nor poverty, nor power outages have been able to provoke protests of the magnitude that one bad marketing ploy by PepsiCo has. Representatives of various strata of society and political associations, communists and the military, the poor and those who considered themselves to be the middle class took to the streets. Everyone was rallied by the "deception" of cola producers.

Marketing campaign failure

The protests were not bloodless. Starting as peaceful actions, as a result of the suppression of demonstrations by the police, they spilled over into street riots, up to the use of hand grenades by the protesters. At least five people died as a result, including several PepsiCo employees. Some forty of the company's trucks were burned or wrecked, and the products now had to be transported by heavily armed guards. PepsiCo withdrew most of its management from the Philippines, and an emergency meeting was held in the capital between CEO Christopher Sinclair and Philippine President Fidel Ramos.

As a gesture of goodwill, each owner of the cap with the ill-fated number 349 was offered compensation of 500 pesos, or twenty dollars. Almost half a million people agreed to the "titmouse in the hands". It cost the company almost $9 million on an original promotional budget of $2 million. From those who did not want to compromise, appeals to the courts rained down; thousands of civil lawsuits and fraud allegations have been filed.

The court denied the applicants the right to a prize for each cap bearing the number 349, but awarded them ten thousand pesos each in non-pecuniary damage. After appealing the decision in the court of second instance, the amount of compensation increased to 30 thousand pesos.

This action has been considered one of the biggest failures in the history of marketing for almost thirty years.

In 2006, the Supreme Court of the Philippines finally cleared all charges against PepsiCo. In the eyes of justice, the company's actions did not contain elements of a crime, and the mistake was not malicious. In total, in the 1992 competition, the manufacturer of soft drinks lost about twenty million dollars and significantly shook its position in the market.

And the 349 incident has gone down in business history as one of the worst and most costly marketing mistakes.